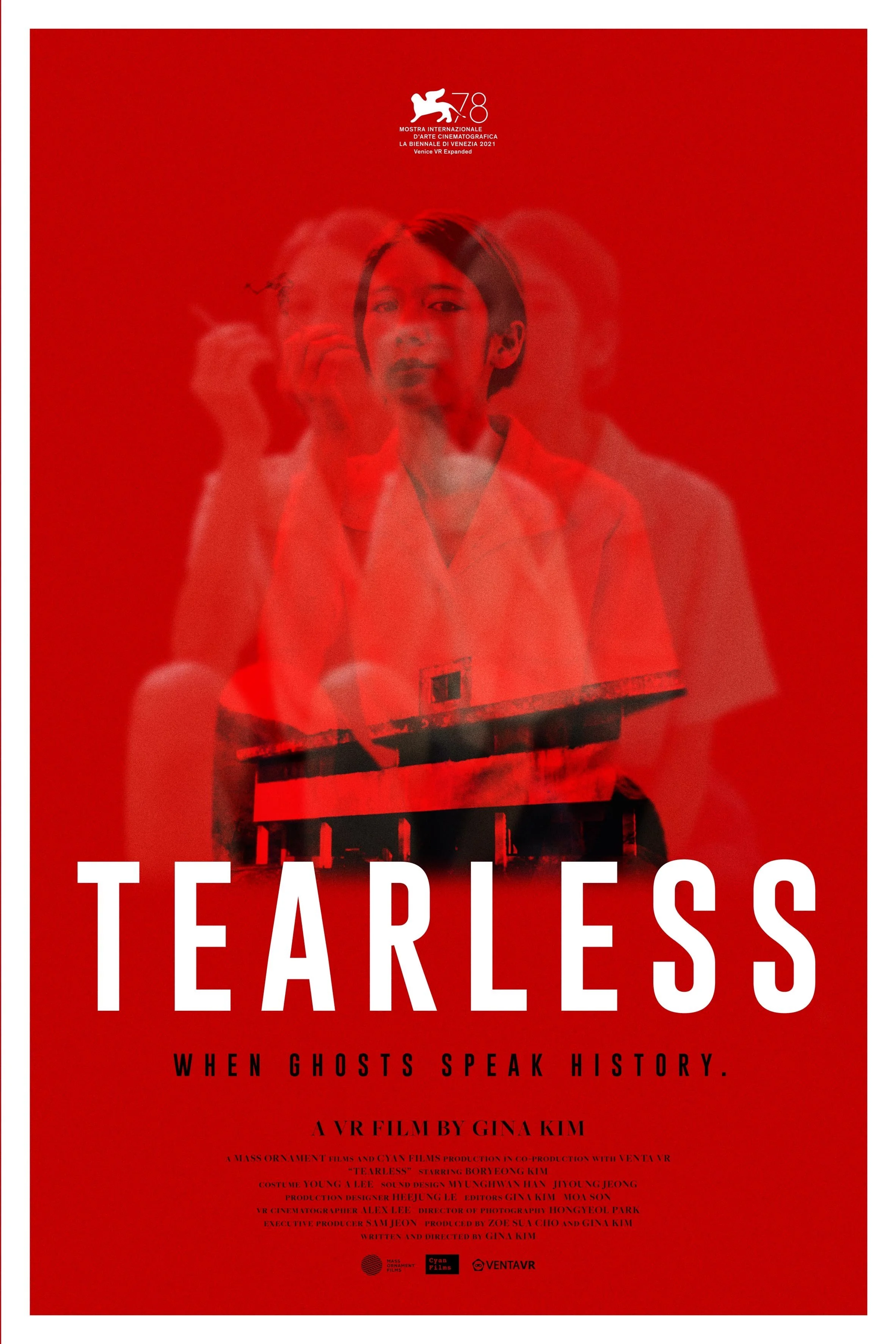

For her work BLOODLESS, Gina Kim received the Best VR Story Award from the Venice Film Festival in 2017. TEARLESS, the second installment of her trilogy on US military comfort women. I had the chance to share an in-depth conversation with Gina Kim about the film and its making-of.

This article is part of a work with GiiÖii Immersive Studio and ixi media in South Korea. Original article: ixi interview (Jul 16, 2021)

Translator: Sharon Choi

J: Could you tell me how you developed this series? And if possible, could you tell me a bit about your next piece in this trilogy?

G: BLOODLESS is about the 1992 murder of Yoon Geum Yi and was filmed in the Dongducheon camptown that still exists to this day. Back in the day, the Korean government conducted STD tests on US military comfort women and, against their will, admitted those who tested positive or those presumed to have it in a detention center to force treatment. TEARLESS is about that center, which is called Monkey House. The building is located at the entrance of Soyosan Mountain. That’s why the Korean title is Soyosan. So in that sense, both films are about place and the female bodies that were trapped in those places. Although I can’t go into details, the third piece will continue that theme and take place in one of the camptowns spread across the nation. It’ll be a story about something that happened at that place and the female body that had to endure it. I think the third film will be the most visual piece I’ve ever created.

J: When you were making BLOODLESS, VR production technology was still in its early phases. How did you come across the medium of VR and end up creating a VR film?

G: I get a bit embarrassed when I get this question, because it appears as if I’m someone who’s really familiar with advanced technology and media. But that’s not true. I’m someone who creates traditional films, sometimes ridiculed by people in VR as “flat cinema.” But I ended up moderating an international forum on VR titled “Virtual Reality Takes on Cinema” in 2016 at the Busan International Film Festival, so I studied a lot about the medium. I did my best to take an in-depth look at it and read the latest papers.

That’s when it occurred to me that I could tell the story of Yoon Geum Yi through this new medium. To be honest, I spent an incredibly long time (almost 25 years) seriously contemplating on how I could tell the story about this murder through the medium of cinema. And every time, I had to abandon the project because of cinema’s limitations in ethical representation. But as I studied the medium of VR, I began to realize that, with VR, it’s possible to experience another’s story without emotionally distancing yourself from the subject of the piece. It would be possible to create empathy without exploitation. That’s when I thought I’d be able to make this film and tell this story through VR. So the story came to me much before, and then the form followed. That’s how I came across VR and ended up creating a VR film.

J: I think you did a great job utilizing the medium of VR. With most VR content, the concept itself is very simple. The basic thought is that the audience is where the camera is. So regardless of whether the audience wants to or not, they end up having the experience together. But I don’t think that intention’s being actualized very well. Because even if the camera is there, the audience can be averse to it or feel a sense of displacement. They might wonder, “Why do I have to be here?” or “Is it right that I’m looking at this? Am I really interacting with something?” It makes you have thoughts like that. So I thought that such simple concepts actually hinder the medium’s powerful potential.

G: You’re right.

J: I think BLOODLESS and TEARLESS show how VR can overcome that. I’m curious if you feel like you were able to actualize everything you planned for the film or if you faced any difficulties.

G: At first, I was quite flustered. I wasn’t someone who worked on VR films, so I only had vague ideas about it. But when I started to actually work on it, I quickly realized the medium was too different for someone who’s only used to 2D cinema to just jump into it. What helped was that I’d studied fine art. I worked with video, media art, performance, and installation pieces so it was natural for me to think of medium as just a tool. I was comfortable with that idea. I always thought that you just need to find the right tools that the story demands.

The first thought that actually came to me once I abandoned the idea that VR is a 360 film was, I did a lot of experimental theater in college, and this is actually similar to theater. The audience is in the middle, and actors and objects can pop in from any corner without you knowing. It’s theater that the audience and director cannot control. And then a whole new world opened up.

At first when my DP and I went to the location, I was like, “let’s shoot that since we shot this.” And then he would tell me, “But you just shot it.” That’s when it would occur to me that this is a 360 camera. I couldn’t get used to it. The director really can’t create a shot flow or control the edit, so close-ups are impossible as well. I had no choice but to let go of the traditional filmmaking process.

To be more specific, the undemocratic aspect of cinema comes from how the director gets to shoot what they want, place the shots together, and only show the audience what they want to show. But when I realized VR is not like that, it felt so fun. The director loses all their autocratic power. And once I realized that you cannot control which direction the audience turns to see, I realized that I had to turn this around and use it to my advantage.

When I created BLOODLESS I had a lot of fun with how the director can’t control what the audience sees, so I was like why not maximize that? At first a lot of people missed the fact that a woman is in the scene. And that’s how it’s supposed to be. Then the piece drives the audience into narrower and narrower alleyways, and in the end forces the audience to completely confront the woman. It’s subtle but intentional in a completely different way than traditional cinema is. I was really fascinated by that although it took a while to adjust to it in the beginning.

J: Using VR’s limitations as an advantage is I think what made BLOODLESS an unparalleled film among the myriad of VR films created back then. VR has the advantage of leading the audience into a world that’s not visible or accessible. So a lot of VR films take place in the wild or deal with the deep sea or outer space.

But I think BLOODLESS and TEARLESS are not really interested in showcasing something to the audience. Especially, since the Yoon Geum Yi case was a very important historical incident and there are still lots to be reconciled and healed, I thought it would have a lot to say about this case. But the running time is short. How will you show and tell this story in that short time? That becomes the question.

But I think the moment you let go of that desire to show, the piece actually became richer. I thought that as a director it might have been difficult for you to just let go of that while using VR. And I think that irony is all in the titles as well. The most shocking scene in BLOODLESS is when looking at the blood, but the title is “BLOODLESS.” And TEARLESS almost drowns in tears, but you called it “TEARLESS.” I thought these decisions you made as a director were what made the pieces so successful. How did you come up with these ideas?

G: Thank you so much for what you just said. With BLOODLESS, as I mentioned earlier, the story came to me first. When the Yoon Geum Yi incident occurred, I was a college freshman, and I was incredibly shocked. I was really young back then. There were a lot of people who protested and resisted over the case—nationalists, human rights lawyers, anti-American activists, people from women’s organizations, and such. We, on the other hand, were just university students.

But when we received the guidelines, posters, and flyers, we were so shocked because there were photos of Yoon Geum Yi’s dead body. The photo of her body wasn’t just on the flyers that we had to spread out. It was all over the media, and I know they are circulating online even now. That made me so angry. I felt like the various slogans printed on the flyers in poor English like “Yankee Go Home” were being branded onto my heart. I think that formed my identity as an artist. It really solidified my identity as a woman who lives in a postcolonial society. And at the same time, I wanted to sort this situation out. I was young, but I still wanted to collect all those photos and destroy them so that these images can never get out again. And I wanted to tell this story properly. The rights that Yoon Geum Yi lost, especially the rights of her image, I strongly felt that I wanted to give her back that right. But there was nothing I could do back then.

Even after I became a film director, I often felt the urge to recreate this story, but I ran into the same roadblock every time. I wanted to tell this story, but realistically there was no way I could tell it without exploiting the victim (and the victim’s image). With a commercial film it’s not possible to tell that story and avoid showing the scene of the crime . So I gave up with all these limitations. But when I came across VR, the phrase that struck me was “absence of the body.” I wanted there to be a lack of the body at the scene. I had this strong intuition that I could tell this story with VR if there’s a lack of the body at the scene and you only see remnants of the murder. So “not showing” was the key word from the very beginning. It was my way of finding a solution to the ethics of representation within a cinematic medium.

TEARLESS is the same too. Women went through such tragedies at Monkey House. There are testimonies out there that tell you about things you don’t even want to imagine. And to me, the key question was always, “How do I get people to feel the events without showing them what happened?” Because the moment you show what happened, it’s once again inflicting violence against those women. It’s exploiting their image, and then I would end up creating something that’s the opposite of what I wanted to do. It would just be reproducing the same method of traditional 2D cinema, so my goal from the beginning was to tell the story without showing, to create empathy without showcasing.

J: Despite the strengths of VR, did you feel any limitations?

G: I did feel limitations. Due to several limitations in technology, it’s impossible to actualize everything you want, but every medium has its own limitations. With VR, there’s a limit to how you can distribute and screen your film. There is some resistance from the audience about having to wear a headset. But with the US military comfort women trilogy, the films were developed and created so that you can’t separate form from the story. The late Professor Hyun Kim, in his book Insight about Totality, summarizes the controversy surrounding form and content. He says, “You cannot separate the gold and the hole with a gold ring.” I think that’s what my US military comfort women trilogy is about. You can’t imagine the work without VR. The content is the medium and the medium is the content, so I’m quite happy about that.

J: I’m sure you want this issue to create a controversy and for people to empathize with it, find it problematic, but VR doesn’t quite have that reach yet. You must have thought a lot about this aspect of VR. Still, the piece won an award at Venice and was successful internationally, so the film did achieve desired results.

G: I had a lot of thoughts about distribution too. I have so much respect for filmmakers who create documentaries that are faithful in relaying information and can educate the audience. I really respect how those pieces rely on the clarity of language. But despite that, the reason I’m continuing this series as VR is because I want to actualize sentiments that are beyond the realm of language and deal with them on a more fundamental level. Instead of delivering a certain story through language and educating the audience, I wanted the audience to be present and become shaken emotionally. That’s why I chose to use the poetic potential of VR and have the piece fall into this realm that’s vague and emotional. There is definitely a distribution limit.

But I’m thankful that BLOODLESS was introduced to many audiences. It was screened at around 80 film festivals. There were screening requests from not only theaters but also various art museums and schools, and there were several special events that followed the screenings. The Eye Film Museum in the Netherlands gathered and screened films and archival footage about US troops stationed in Korea and held debates around the issue and a panel that discussed how the presence of US military in South Korea was represented in cinema and TV, both in Hollywood and South Korea. Institutions like Amnesty International also talked about the film. It occurred to me that there are so many ways to change the world through film and video. Once it’s released to the world, it creates opportunities for a lot of people to talk about it, so I’m not as frustrated as I was about distribution.

J: Earlier, you brought up the issue of showing the female body, and I was shocked by the approach this film took to that issue when I saw it. In terms of the image, it’s very minimal. You just shot an empty space that’s in ruins. Although we don’t see any reenactments or interviews of people who were there, you actually feel the shocking tragedy that took place in that space. It gave me goosebumps. Although you don’t refer to anything specific about the incident, the way you were showing the building made me feel like I was looking at the bodies of the women who were victimized there.

It’s a space that’s so decrepit that you feel like you can’t even take a single step. I think you can understand that space as a metaphor. “This space is like the bodies of the women who were here. The acts we committed are like this space. We’re looking at something that’s damaged beyond the point of repair.” I had goosebumps once I had this thought. That’s how I felt you put so much attention to delicate details with this piece. Could you elaborate on that? Film directors usually want to show things directly. You put close ups or put together a sequence that climaxes at a certain point.

G: (laughs) Right, with the help of music too.

J: But you gave up all of that. All this might not be delivered well without it. The audience might not get those metaphors and symbols, but you pushed through. You must have had a sense of assurance or a goal that you wanted to achieve.

G: I thought a lot about the issue of ethical representation. With TEARLESS, the questions I had about the ethics of representation were a little different from BLOODLESS. Of course, there were many ways to make this piece provocative and sensational. But I didn’t want to. I just wanted to deliver the initial shock I felt when I visited the place in 2015 or 2016. I had a sense of assurance. You can feel it if you just come to this place. I’m just a normal person and I could feel it the moment I entered the building. I was sure that even if you don’t know exactly how this space was used, you would get a feel of what kind of place this was.

And in the end, this film has a subtle narrative. What’s important is not the building, but the women who were trapped inside—the women’s bodies and the time these women had to endure. I thought a lot about how to incorporate temporality into this film, and I found the answer in the daily itinerary. When I first visited the building, the daily schedule was still on the wall. It’s not there anymore, but it listed a timetable—wake up at 7am, breakfast at this time, treatment at this time, education at this time, work out at this time. It was a handwritten timetable of a schedule that was enforced by the administrators, and although the building is heavily damaged, you still see traces of that itinerary in the building. I thought their daily schedule made it clear what these women had to endure during all that time they were trapped in there. And I didn’t want to add anything scandalous. I wanted to introduce the space, bring in props that just hint at what those spaces were used for, and add temporality through them. That’s how I created the story.

To be honest, I didn’t think about using the ruined building as a metaphor for the women’s bodies. I’m actually opposed to the idea of using the women’s body as a metaphor. I actually think this building should be preserved for a long time and become a memorial that people can visit. But the place has changed so much since I first visited in 2015 and 2016. It’s filled with trash, and heavily damaged. I had a lot of conversations with my art department on how to approach and shoot this space. We were strict about the principles of if it was in the building, leave every damage untouched, and if you find any trash that appears to be from the building itself , leave it. If it’s trash that people later on brought from outside the building, we can get rid of that. We shouldn’t hammer even a nail on the wall or even tape anything. There was a lot of graffiti on the walls but we erased them with VFX. We had to go into this project with the intention to restore the space, so I asked the crew members not to touch even a window. A lot of the windows were already pretty shattered, and I knew once you touch a part of it the whole thing will come crashing down. So it was like we were all walking on eggshells when we were shooting the film. I’m grateful to the crew that worked on this with me because I only had one thing to tell them: please treat this building as if you’re treating the women’s bodies. I’m really grateful that everyone respected that request.

J: Wow, the graffiti on the walls were all erased with VFX.

G: (laughs) Yes.

J: You do see graffiti in the middle of the film. That was memorable. I didn’t realize that the place was marked with a lot of graffiti afterwards.

G: Yes, if it were just your average graffiti, I would have left it. But the actual space was so heavily damaged with graffiti to the point it became too much of a distraction for the audience. I was conflicted on whether or not I should erase the graffiti. But I ended up deciding that it would hinder the audience from immersing themselves into the film. Because the graffiti were mostly words, the audience would spend too much time reading those words and thinking about them. So we removed them with VFX.

J: With BLOODLESS and TEARLESS, the audience exists in the space as a ghost without a body. You’re there like a ghost, but the moment you meet eyes with the actor—so the moment this piece recognizes the audience—you get the feeling that you’ve been summoned into this issue. And that “acquired sense of self” witnesses the floor (where the blood pools). I thought that was great direction on your part, and it was the point where it acquired a different level of prestige compared to other VR works with relatively simple concepts. There’s aesthetic and thematic value acquired through the act of not showing. But earlier you said that the last part of your trilogy will be a very visual piece. I wonder if you’ll continue this effort through a different style, or if you’ll take a new approach and lead the audience to a different destination.

G: In short, I will be continuing the same effort. By visual, I mean it in a very ironic way. With BLOODLESS and TEARLESS, you end up imagining what you don’t see, and so you’re actually left with a more powerful impression. With TEARLESS, you see props, and you don’t see what they’re used for, but you still end up imagining the acts. So the third piece will be very visual in that sense. Not seeing something makes the piece more visually powerful. But I want to be more active in using lights and things like that. I want to talk about this irony where you know you’re seeing something but you’re not actually seeing it.

Because, you mentioned the word “ghost” earlier, and if you think about it, with BLOODLESS and TEARLESS, the presence of the women you come across is spectral. When you lock eyes with this woman, you feel like you’re becoming one with her. With BLOODLESS, you don’t feel like you’re on those streets shot in 2016. You are transported to the room in 1992 where that woman was brutally murdered. You experience being possessed. Similarly in TEARLESS, from the moment that woman looks at us, we start hearing the sounds of that woman. From then on, you become one with her and start to intimately experience what that woman goes through from up close, and I think that will continue in the third film as well.

J: VR production has gone through a lot of technological changes, like with the camera, stitching, and post-production. I’m sure you felt a big difference between BLOODLESS and TEARLESS. Obviously, your directing intentions will remain the same, but do you hope that you’ll be able to create the film in a better environment next time?

G: Yes, I think that’s right. BLOODLESS was shot on six GoPro cameras, so there were significant issues with resolution and picture quality. Thankfully, because the movement of the spectral figure was the most important element in that film, the loss in resolution was somewhat tolerable, although I was incredibly frustrated. When I created TEARLESS, however, I was able to shoot in 8K, make subtle adjustments, and create the visuals that I wanted. Technological developments like that allowed the story to become richer. I think by the third film of the trilogy, new possibilities will be even starker. I think technological development will enable a more powerful portrayal of that “sense of presence becoming visible through invisibility.”

J: I suppose watching this trilogy will be like watching the development of VR production technology.

G: Well, that would be great. (laughs) But I’m not really the best in understanding the technology in great depth.

J: It was difficult to bear how long it took for TEARLESS to come out after BLOODLESS. Will we have to wait that much longer for the third film to come out?

G: I do think I need to make it sooner than that, but honestly, it took so long because of production costs. With BLOODLESS, the producers, including myself spent their personal funds, and Venta VR provided in-kind support and post-production services. It was a film I was barely able to make through various grants I received from my university in the US. The stitching process was extremely difficult too. It felt like I wasn’t just stitching the images together but the budget too. It was a very patchy, DIY process. It was a little smoother to create TEARLESS, but it still took a long time to gather the funds for the film.

It’s a shame that it took such a long time. But it’s a difficult and sensitive topic, and I knew I couldn’t change the aesthetic principles that were at the foundation of this film. I strongly felt that I had to protect that. I did receive investment offers, and that would have helped in creating the film sooner, but I often thought that the strings attached to the fund (IE: make it more commercially viable) would end up compromising the principles that I set for myself. So the conclusion that I came to is that it’s right to tackle a difficult piece of work through a difficult process. Even if it takes time, this is a difficult piece, so the process shouldn’t be any easier. That’s how difficult it was to create this, and it took a long time.

J: But I suppose if you think about when this case originally occurred, the years in between your films aren’t that long of a time.

G: You’re right.

J: This issue demands that we spend a long time dwelling on it, and we’re going through that time together instead of just quickly wrapping up the story. I hope in the meantime audiences get the chance to see this film and discuss what needs to be discussed. To be honest, film festivals are like pop-up exhibitions that only go on for a week or two, and it is difficult for VR films to reach a wide audience. So I’m curious about how you plan on showcasing this film after the film festival, since by the time this interview is out the festival would be over. Could you tell us where we can find TEARLESS or BLOODLESS after the Venice VR Expanded exhibition?

G: The schedule isn’t set yet, but I think TEARLESS will be shown at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art for quite a period of time. We screened BLOODLESS at MMCA before, but the screening period was so short that there were a lot of complaints. It’s not like traditional films where hundreds of people can see it at the same time. So we’re going to showcase it for a while and create more opportunities to have Q&As with the audience. So we do have off-line exhibition plans lined up. I think it’ll be screened at several other film festivals as well.

BLOODLESS is currently being screened for free at the MIT Open Doc Lab online. It’s going on for a year. They selected ten VR films that they deem meaningful and valuable and have been exhibiting them online. I think that’s the best way to screen the film in this pandemic era. At The National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art Korea, it will be showcased off-line, but I hope on-line exhibitions happen at the same time. I’ve been talking with art museums about how it would be great to have an interactive platform where I can communicate with audiences online.

J: BLOODLESS and TEARLESS are live-action films shot with a camera. But it’s not that easy to create a VR film using live-action footage so several films are actually made in animation style. Once you use animation, there are several strengths that you acquire. The audience is free to interact and you don’t have to stitch images together, so you can perfectly actualize the visuals of that world. There are documentaries using that advantage these days and works that deal with interesting themes. Are you interested in things like that? Have you ever thought about creating the film through animation due to the difficulties of live-action VR?

K: Of course. I think animation is the only field I haven’t tacked yet. (laughs) I’ve tackled several mediums and genres, except animation. And I’m quite interested in experimental animation. The VR animation films that I haven’t seen that many of were close to 3D animation. But I think that if I take a more experimental approach and mix live-action with experimental animation through VR, I can create a powerful and fantastical experience that truly resembles dreams. To me, it’s not really important whether something is live action or animation. What’s important is immersion. I think that’s the value of cinema—how deep the audience can immerse themselves, and how closely the audience can empathize with what they’re seeing. That’s my ultimate goal. So I’ve been thinking about how I can incorporate animation.

J: A lot of directors and artists have an aversion or fear against technology. With VR, AR and things that combine various fields, I think they are like “I don’t really know technology.” But when I see your work, I think what comes first is not understanding technology but what you want to express.

G: Thank you. (laughs) Everyone has different thoughts on this, but content and form, in other words, mediums and the themes they build cannot be separated. Medium is just a tool. I’m neutral when it comes to mediums. When VR technology first came out, a lot of people were concerned that it would be used to create pornography or exploitative videos. But I turned that around to use it as my advantage through BLOODLESS and showed that VR is the best medium to empathize with victims. I strongly believe that medium is neutral and everything depends on the intentions and values of those who use it. It’s my own belief as an artist. I don’t think it’s really meaningful to debate on whether I’m right or wrong. The future is not set. When we actually practice what we believe is right, we come to manifest our beliefs. It’s a future of will. When I created BLOODLESS, people asked me what I think about the future of VR, if I think this can become a medium for social justice and social change. I answered, “It can, and what’s more important is that it must.” I think this applies to all other mediums.

J: I don’t think you can skip talking about sound since sound is so integral to TEARLESS. I’m curious about what kind of thoughts you had on sound when you were creating this piece, what kind of direction you gave to the sound director, and what ideas and experiences you had regarding sound during the production process.

G: Sound is what drives the narrative in this film, because unlike traditional 2D films, there was no such thing as a shot flow through editing. You can’t create things that force someone where to look and what to focus on. There aren’t any inserts or close-ups, and so I thought that I had to build everything through only sound. With BLOODLESS, I established the presence of the spectral figure through the sound of footsteps. With TEARLESS, I wrote the script thinking about how sound builds the narrative from the very beginning. So from the screenwriting stage, blood would be at the center of BLOODLESS and tears would be at the center of TEARLESS. These are both fluids coming out of women’s bodies. How will I create the narrative with this at the center? I wanted to build the narrative through sound, so in the end, I thought of water sounds. From the beginning, you keep hearing water sounds that remind you of a cave, which is completely incoherent with what you’re seeing in the building. And in the end, that becomes amplified and makes the audience immerse themselves. Those ideas were already present from the screenwriting stage and it’s essentially the plot of this film.

When I had a meeting with the sound designer, I told him that this water sound, this strange sound shouldn’t be considered as sound effects. In our film, this is the dialogue and the story. This is an unorthodox approach in traditional narrative films, let alone VR films. But he was really accepting of it. My sound designer was Myung Hwan Han from Wave Lab, and he created a rough skeleton of the soundscape and then added a ton of effects that are barely detectable to really liven up these sounds. If you listen carefully, you hear these strange ambient room tones that you think only exist in outer space. Detailed sounds like that underlie every scene and culminate into music. He tried very hard to amplify the audience’s emotion and really paid a lot of attention to detail working on it. I’m grateful.

During sound mixing, I had to briefly go to the US. The sound designer was very considerate and helped me listen to the sounds from the mixer remotely through earphones at home. I was so happy during this process. The sound itself is the narrative. To us, the water sounds and the ambience are the dialogue. The sounds of the environment are the lines. Because the sounds of this building are the story. He did such a great job actualizing it. I hope people get the chance to get the stereo sound and listen to it with earphones. That’s how tightly built the soundscape is and it’s structured very beautifully like music.

When you watch the film, you hear a bunch of tiny sounds. There are a bunch of leaves and trees that have penetrated the building. To emphasize that, we added sounds of leaves rustling in the wind. And in scenes where you see a mess in the bathroom, you hear flies. Those sounds didn’t exist from the beginning. They sound very realistic, but we all designed and added them. That could spark some controversy in that sense. Some people can question why we designed the sound and added them when this is a documentary. But as I mentioned earlier, I think this is a question of how truthful you can be in recreating reality. I think it could be problematic if I randomly added strange sounds that I never even heard of when I was at the location just to amplify sentimentality. But I went to the location several times to write the script. I heard those sounds whenever I went, but we couldn’t really catch them when we went to film. So in a way, we added those sounds to truly recreate reality.

J: I think there are so many metaphors within the film. Things that exist but which we do not see. History and acts that are of our past but which we do not see but still exist now. And things that we do not hear now but have the duty to hear.

G: The ironies and metaphors you pointed out, I think, are aesthetic strategies that really suit this film. This topic of US military comfort women, US troops stationed in Korea, camptowns, and the local topography of US bases in themselves embody that. Their presence represents what you find in parentheses in a sentence.

South Korea is now a well-off country. It’s practically a first-world nation. But most people have forgotten that there are US troops stationed here. We know it, but they’re not that visible. People think that they exist somewhere and that they must be occupying a certain area. We all know it, but we don’t really think about it. But it definitely exists as an undercurrent, a strong presence that drives this society, and there are women who had to make incredible sacrifices because of that. We don’t hear their voices. But so many women were damaged, and they still exist in our society. That’s so strange to me. It’s so strange that this building, the Monkey House still exists. I’m scouting locations and doing research for my next film, and I find that these camptowns still exist. But we don’t know about their existence. They exist but at the same time they don’t. They are visible but at the same time they’re not. These issues lie within this peculiar condition, so I think this aesthetic strategy was appropriate for it.

J: Yes, you’re right. At the end of TEARLESS, we see text talking about when the building closed…

G: 2004.

J: Yes, in 2004. That number 2004 felt so bizarre as well.

G: Yes, it’s recent. Ultimately, that’s the reality that we live in. People say that in a post-capitalist society, we live in different time periods depending on which class we’re in, even though we live in the same region. I think that applies to this. TEARLESS is a story about those who’ve been marginalized, who couldn’t enter mainstream society, and those without the economic ability, and thus have been rendered invisible. People who live in semi-basement or rooftop homes, you can’t really see them. It’s quite frightening how some people become invisible within the same neighborhood. It’s the same issue.