[MUBI] Faces in the Crowd: “Comfort Women” on Film

Japan and Korea have sought to strike sexual slavery from the historical record, but survivors have found shelter in other archives.

Floating Clouds (Mikio Naruse, 1956).

In the opening scene of Mikio Naruse’s Floating Clouds (1956), a group of repatriated Japanese civilians disembarks from a shabby boat. After two brief wide shots, Naruse cuts to a medium shot to introduce the film’s protagonist, Yukiko, singling her out from what is otherwise a crowd of anonymous faces. But the film’s screenplay elaborates on those who walk alongside Yukiko:

Returnees from South Asia are getting off the ship. Among the crowd of women, which consists only of comfort women, geishas, nurses, typists, clerks and the like, there is also Kõda Yukiko, who is not outfitted with proper winter attire.

“Comfort women” is a name given to women and girls forced into sexual slavery at the hands of the Japanese Imperial Army. According to Yoko Mizuki’s screenplay, some are present in the crowd, but it is impossible for the viewer to discern them. The exact number of “comfort women” is up for debate, but estimates range from 200,000 to 500,000. Though they came from all over the Japanese Empire, the majority of the victims were Koreans. In Korea, it is a common practice to put the euphemism by which they were known in quotation marks to highlight the heinous cruelty of what the word “comfort” implies in this context.

The mere inclusion of “comfort women” in Mizuki’s screenplay is striking since it was a taboo subject at the time. To this day, members of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP)—postwar Japan’s conservative party, which has dominated electoral politics since it was founded in 1955—either flat-out deny the existence of the “comfort women” system or downplay the state’s involvement in organized sexual enslavement. The South Korean right often parrots LDP’s official stance under the pretext that articulating and reckoning with the history of “comfort women” would irreparably damage diplomatic and economic relationships between the two countries. The surprising mention of “comfort women” in the Floating Clouds screenplay is all the more notable because they are omitted from the novel on which the film is based. Between 1941 and 1943, the book’s author, Fumiko Hayashi, worked as a pro-imperial war correspondent in Manchuria and Southeast Asia, and she likely encountered these enslaved people at the Japanese military bases she visited. The absence of the victims in her novel may not be deliberate obfuscation, but it renders her depiction of Japan’s imperial history incomplete.

Floating Clouds (Mikio Naruse, 1956).

Although both Korea and Japan have sought to strike “comfort women” from the historical record, they have still found shelter in other archives. As is evident in the fact that the viewer cannot discern their presence in the opening scene of Floating Clouds without having read the screenplay, their memories await excavation from the rubble of history. Philosopher Jacques Rancière writes in his essay on Chris Marker’s The Last Bolshevik (1992) that memory is not a mere repository for recollections and brute facts; it is always constructed and arranged according to a predetermined principle that privileges certain voices over others. The reservoir of films about “comfort women” is small, but taken together, these fictional depictions and nonfictional testimonies form a constellation of memories, itself a particular kind of film historiography—what Rancière calls “fictions of memory” that want to bear witness to the forgotten and the silenced.

As the Japanese Empire expanded and the situation in the Pacific Theater intensified, the number of conscripted men grew accordingly. Among them were Yasujiro Ozu and Seijun Suzuki. In a diary entry from April 1939, Ozu, stationed in Manchuria at the time, writes: “A ‘comfort station' was built here about three days ago. […] It is an irresistible entertainment of the peninsula.” None of Ozu's postwar films include "comfort women,” and he never publicly discussed any encounters with them. Suzuki was much more open about his experiences with the enslaved people. “To avoid the outbreak of a revolt because of sexual deprivation [...] the army staff had also considered it strategically necessary to supply us with three army prostitutes,” says Suzuki in an interview collected in Shiguéhiko Hasumi’s 1991 monograph, Seijun Suzuki: The Desert under the Cherry Blossoms. His decision to adapt Taijiro Tamura’s novel Story of a Prostitute in 1965 with explicit reference to “comfort women”—only implicit in the novel and in Senkichi Taniguchi’s 1950 film adaptation, Escape at Dawn, co-scripted by Akira Kurosawa—suggests the film was much more than a studio assignment.

Tamura’s novel, a representative work of “literature of the flesh” (nikutai bungaku), treats the human body as a theater of biopolitics in which corporeal pain and pleasures have the power to overcome the totalitarian state. In translating Tamura’s words into moving images, Suzuki keeps the bodily pain and pleasures, but rejects Tamura’s political premise via the thoughtful interplay of wide shots and close-ups. Story of a Prostitute follows Harumi, a “comfort woman” at a remote outpost in Manchuria alongside six other women, including a nameless Korean. The film shows the many acts of brutality Harumi has to endure in wide shots, and sparingly cuts to close-ups of her face in their aftermath, thus revealing her physical and spiritual deterioration under the boot of Japanese fascism. Conversely, Tamura’s novel obsesses over the liberatory possibility that sex opens up for the soldiers, but ignores the fact that this “liberation” becomes possible only through unleashing imperial violence on the women. By lifting the veil of Tamura’s romanticism, Suzuki’s film squarely repudiates LDP’s historical revisionism of the institution of “comfort women.” It is no coincidence, then, that the film’s only anti-imperialist character, Uno, is not interested in carnal pleasures, and bestows on the Korean “comfort woman” the level of dignity otherwise reserved for her Japanese counterparts. The unnamed Korean woman gets the final word in response to the news of Harumi’s suicide: “The Japanese want to die in haste. No matter how hard it is, we’ve got to live.”

Story of a Prostitute (Seijun Suzuki, 1965).

Indeed, the survivors of the Imperial Japanese military’s sexual slavery kept on living after the Pacific War concluded, though mostly in silence due to shame and stigma. That their traumas were mercilessly exploited in softcore pornographic films—Your Ma’s Name was Chosun Whore (1991) being the worst offender—made it all the more difficult for them to come forward and speak openly about what they went through. But as the country’s ruling military junta started to weaken in 1987, South Korea underwent a series of sociopolitical transformations. The constitution was amended to guarantee open elections, freedom of the press, and protection of basic human rights. Encouraged by the growing women’s movements and a maturing public understanding of sexual violence across Korean society, Kim Hak-sun came forward in 1991 with the very first public testimony about her experience as a “comfort woman.” Kim’s press conference, held on the eve of National Liberation Day of Korea, was a direct response to a Japanese government representative’s 1990 statement that there was no coercion involved when recruiting “comfort women.” She held another conference in Tokyo on December 9 of that year. Kim’s statements were televised in both countries, and led to a swell of testimonials coming from several other countries formerly occupied by Imperial Japan. Every Wednesday since 1992, former “comfort women” and their allies have gathered in front of the Japanese Embassy in Seoul, demanding an unconditional apology and reparations from the Japanese government.

It was around this time that South Korea’s first feminist film collective, Bariteo, was active. Although short-lived, the collective produced two films in the early ’90s that examine the reality of women’s labor in the country, and held workshops to promote an alternative cinema that puts feminism and collectivism into practice. Shortly after Bariteo disbanded in 1992, Byun Young-joo, one of its founding members, began working on her first feature-length film, A Woman Being in Asia (1993), which investigates how sex tourism in Jeju catered to affluent Japanese businessmen. While interviewing local sex workers, Byun came across a woman who had turned to prostitution to pay for her ailing mother’s medical bills. The mother, it turns out, had been a “comfort woman.” Struck by how Japanese imperialism had shaped these two women’s lives over two generations, Byun soon paid a visit to the House of Sharing, a residential commune for former “comfort women.” While living with the survivors on site for a year, Byun developed her next project, The Murmuring (1995), which was made possible largely through grassroots merchandise sales and donations of film stock. It became not only the first film to collect testimonials from former “comfort women,” but also the first feature-length documentary to receive theatrical distribution in South Korea.

The Murmuring (Byun Young-joo, 1995).

Aside from its film-historical significance, The Murmuring is remarkable for the kind of historiography that it practices. While the film foregrounds the survivors’ testimonies and their activism, Byun devotes as much screen time to their everyday lives, capturing the group at a dinner party, working on paintings, singing, and dancing. Thanks to Byun’s insistence on the present tense, the film manages to document former “comfort women” as people whose lives are still unfolding, rather than fragments of a distant past. At one point, Byun asks the women what they think they would have been doing had they not been conscripted into sex slavery. Their answers vary widely: singing on stage, making visual art, being healthy enough to take frequent walks, going to school, and taking up arms to defend their country. The residents of the House of Sharing imbue the screen with the weight of tragic history, as well as the possibility of a future beyond shame and defeatism.

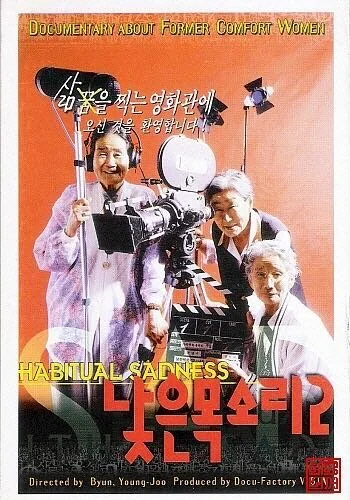

Eight months after the completion of The Murmuring, Byun received a phone call from the film’s subject. The commune had since moved to a new location, and they suggested that Byun shoot another movie. One of the residents, Kang Duk-kyung, had recently been diagnosed with a terminal case of lung cancer, and it was Kang’s wish that Byun document her final months. The resulting film, Habitual Sadness (1997), is built on a collaborative filmmaking model championed by Bariteo. Byun fondly recalls how the survivors spent a week persuading the director and her crew to document the pumpkin harvest, and argued among themselves about framing choices. Working alongside them, Byun asks why they wanted her to film them harvesting pumpkins. “Because we grew these ourselves.” Byun’s follow-up question: “How would you like to appear on screen?” The answer: “I want people to see that I work hard like a cow.” This shot encapsulates the three different forms of labor that Habitual Sadness wants to celebrate: the harvest, the collective authorship of Byun and the survivors, and their reclaimed autonomy over their identities, disentangled from their past lives as "comfort women." On the film’s official poster, one of the survivors holds a boom pole, another a camera, and a third a slate.

The House of Sharing’s mourning for Kang’s terminal diagnosis is soon followed by fellow commune resident Lee Young-sook’s 1997 television interview, in which she declares: “I want the world to know our struggle. We don’t want to die so easily. We’ll live for long. We are strong. Japan has made us this way, and we will be stronger.” Of course, the remaining survivors knew that they did not have much time left either. There are now only nine known former “comfort women” still alive in South Korea; in 1997, that number was closer to 200. Byun made one more film with the survivors, My Own Breathing (1999), in which they take on more agency by interviewing each other. During a Q&A following the twentieth-anniversary screening of The Murmuring in 2015, Byun told the audience that she hoped her “comfort women” trilogy would serve as a cinematic archive of survivors’ memories, to counter the dominant historiography that wants to forget their sufferings, and to situate their struggle in the contemporary women’s movement. It is for this final reason that Byun concludes Habitual Sadness with an intertitle detailing some dismal statistics about rape and sexual assault cases in South Korea. As the history of “comfort women” coalesces with the reality of modern-day sexual violence, the survivors’ political struggle becomes a crucial part of our own.

Top: Habitual Sadness (Byun Young-joo, 1997). Bottom: Theatrical poster for Habitual Sadness (Byun Young-joo, 1997).

Emily Jungmin Yoon, a poet and translator from Busan, pursues a similar project of memory construction in her 2018 poetry collection, A Cruelty Special to Our Species. In the Hwang Keum-ju section of the poem “Testimonies,” Yoon writes:

The day of liberation Suddenly,

no sound of horses the last soldier

stood in the kitchen “Your country is liberated,

and my country is sitting on a fire.”

So I left the barracks

I walked

I was alone and walked all the way to the 38th parallel

American soldiers sprayed me with so much DDT

all my lice fell off.

Where Byun superimposes the history of “comfort women” onto the rape culture of contemporary South Korea, Yoon sheds light on the thread that links Imperial Japan and the United States. The peninsula that was once occupied by Japan’s Imperial Army is now home to Camp Humphreys, the single largest US military base overseas. The fiction of memory created in A Cruelty Special to Our Species narrates how the new imperial power buried the old, then put on the dead emperor’s blood-soaked clothes.

In their introduction to Dangerous Women: Gender and Korean Nationalism, Elaine Kim and Chungmoo Choi propose that Korea in the twentieth century should be read as “a palimpsest of multiple layers of Japanese colonialism and [...] U.S. hegemony, which superimposed its systems on the political and social infrastructures of Japanese colonial rule.” Having acknowledged Imperial Japan’s claim on Korea in exchange for control of the Philippines as part of the Taft-Katsura Agreement in 1905, the United States wasted no time setting Korea on fire. During the Korean War, the American military freely tested the early prototypes of napalm. Among the “infrastructures of Japanese colonial rule” that were repurposed by Korean and American militaries during this period were “comfort women.” It is darkly illuminating, then, that Lee Joon-ik’s historical drama Sunny (2008), which demonstrates the mutations of “comfort women” under the new imperial rule, is about a “consolation performer” during the Vietnam War. The film’s protagonist Soon-yi travels to Vietnam in search of her husband, who has enlisted in the South Korean Army, and becomes a wartime starlet by the name of “Sunny.” The “consolation” part of the Korean word for “consolation performer”—위문 (慰問)—shares the Chinese character 慰 with the “comfort” part of “위안부 (慰安婦),” which means “comfort women.” In effect, the word 안 (安), the infrastructure built by Imperial Japan, was scrubbed off and replaced with 문 (問) by the South Korean government in service of its new master.

Sunny (Lee Joon-ik, 2008).

With full cooperation from the US-backed South Korean military juntas, the American military turned several towns neighboring its bases into entertainment districts of sorts, where licensed sex workers, many of whom were enslaved, could service the American soldiers. Dongducheon, one of the more renowned camptowns in the country, is both the subject and the Korean title of the first entry in Gina Kim’s VR trilogy, comprising Bloodless (2017), Tearless (2021), and Comfortless (2023). Each entry visits a certain locale where the “comfort women” of the American military worked. In one case, they were forcibly detained in a medical facility; some were murdered. . Presented in 360 degrees and in 3D, these pieces place the viewer, usually seated in a swivel chair, in quiet streets, abandoned buildings, and empty bars. Hovering over them like a ghost, the viewer can survey these sites of medical abuse, sexual exploitation, and murder.

Kim was a first-year student at Seoul National University in 1992, when the brutal murder of “comfort woman” Yoon Geum-yi by an American serviceman inspired a wave of anti–US military protests. Some on-campus organizations circulated the images of Yoon’s mutilated body in an attempt to drum up anti-American sentiment. Kim saw the circulation of such images as another form of exploitation, and this ethical concern about representation led her to virtual-reality technology, with which she memorialized Yoon in Bloodless. In an interview with Jay Kim, she posits that VR filmmaking opened up the possibility of “empathy without exploiting the other.” As the viewer navigates spaces where “comfort women” suffered and died, they must reckon with the history of these atrocities without the aid of dramatization. They are no longer a voyeuristic spectator, but a witness to the material reality that allowed such things to happen. Kim’s VR films ask that we reconstruct these memories in order to prevent what Emily Jungmin Yoon cautions us about in the fourth iteration of “An Ordinary Misfortune”: “she will be girl, girl is gravel and history will skip her like stone over water.”

Kim’s resistance to voyeuristic spectatorship finds its most articulate form in Comfortless, set in “American Town,” a camptown near the US Air Force Base in Kunsan. The film became “a race against time to archive this history,” as noted in the director’s statement, when the redevelopment plan for the camptown was announced during preproduction. Comfortless plants the viewer in empty bars that seem to have shuttered, and has them roam around this ghost town. Occasionally, a woman can be seen as a reflection in the various bars’ mirrors and surfaces. At the end of the film, though, she appears not as a reflection, but tending laundry on the line in a narrow alleyway. She makes eye contact with the viewer: “Who are you?” she murmurs. As we stand before her image, the terms of our spectatorship are immediately challenged—but the woman disappears before we can respond to her question, and our answer or lack thereof can only be addressed to ourselves. The ending of Comfortless essentially holds up a mirror and reflects back at us our relationality to the history of “comfort women.” After all, her reality is our reality too.

Comfortless (Gina Kim, 2023).

It was Park Chung-hee, the third president of South Korea—who had seized power through the US-backed coup on May 16, 1961—who greenlit the construction of “American Town.” As a young man, Park was trained at Manchukuo Army Military Academy. In order to gain admission to the Japanese military academy as a Korean, he swore a blood oath, pledging his allegiance to Imperial Japan. Park’s rise to power in 1961 was, in effect, the second Taft-Katsura Agreement. No other Korean films articulate this history more succinctly than Im Sang-soo’s The President’s Last Bang (2005), which satirizes Park’s final hours before his assassination in 1979. Although Im’s film does not address “comfort women,” it holds the South Korean right responsible for its complicity in assisting the imperial forces that implemented the system. An early, furtive scene of three young women taking off their bikini tops is revealed to be shot from the POV of a secret service agent who manages Park’s escorts. In a subsequent scene, the film links the former president’s sexual exploits to his collaborationist past. Upon hearing the chief secretary’s disapproval of promiscuity among government officials, Park says, “A man doesn’t question what another man does with his crotch.” This line, and the majority of his dialogue throughout the film, is delivered in Japanese. By depicting Park as a lynchpin between the old and new imperial interests, Im insinuates a parallel relationship between state apparatus and sexual exploitation.

On October 26, 1979, Kim Jae-gyu, the director of South Korean CIA, shot the president twice in his safe house. When the first bullet hits Park’s chest, Im opts for a medium close-up of the president at eye level. With the second shot, however, the camera assumes a low angle, looking up at Park’s head with a revolver pressed against his temple, as though the viewer is below a tall statue. Right before pulling the trigger, Kim addresses Park using the latter’s Japanese name, Masao Takaki. The first bullet kills Park’s corporeal body. The second bullet kills Park Chung-hee, the mythology. Im opts for a carefully choreographed crane shot to track Park Seong-ho, the secret service agent tasked with supplying the president’s escorts, gliding around the safe house to survey the carnage from a bird’s-eye view. Seen from a great height, the dead bodies look more like dolls than real people, let alone mythological figures. By foregrounding the artifice of his own cinematographic choices, Im strips the night of Park’s assassination of its status as a sacred tragedy, and effectively creates a counter-fiction of memory against the popular narrative, upheld by both conservatives and liberals in the country, that Park was a tough but benevolent patriarch who lifted South Korea out of poverty.

The President's Last Bang (Im Sang-soo, 2005).

But Im’s counter-fiction came with a hefty price tag. Shortly before the film’s theatrical release, Park Chung-hee’s children Park Ji-man and Park Geun-hye, the latter of whom would become president herself in 2013, took the film’s production company MK Pictures to court, demanding an immediate injunction. The court denied their injunction request, but ruled that the archival footage used in the film’s opening and ending scenes must be edited out. During Park Geun-hye’s presidency, the entertainment and arts blacklist included Byun Young-joo, Lee Joon-ik, and Gina Kim. In 2015, Park and Shinzo Abe “finally and irreversibly,” as per then Japanese Foreign Minister Fumio Kishida's statement, settled the diplomatic dispute over the history of “comfort women.” Abe offered eight million US dollars and a tepid apology devoid of legal accountability. In return, Park agreed to never bring up the issue via Korea’s official diplomatic channel with Japan. In 2023, the year Comfortless came out, the South Korean government spent more than eight billion US dollars to keep the American military stationed in the country. Dongducheon is rapidly gentrifying, and many of the shops and bars Yoon Geum-yi passes by in Bloodless have disappeared. As our temporal distance from this history widens and its material evidence deteriorates, the task of building collective memory becomes that much more pressing.

— Jawni Han, 25 April 2024

For more information, please click here for the original source.